Git

Subscribe to our newsletter

📬 Receive new lessons straight to your inbox (once a month) and join 40K+ developers in learning how to responsibly deliver value with ML.

Intuition

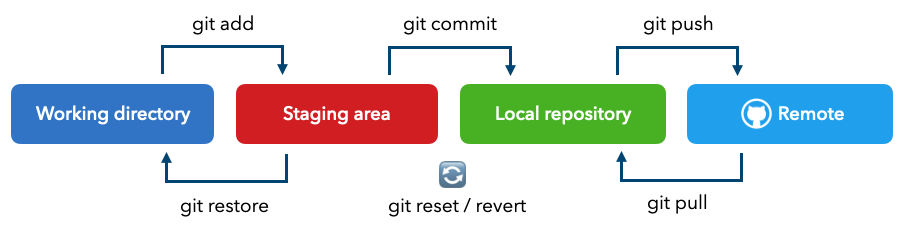

Whether we're working individually or with a team, it's important that we have a system to track changes to our projects so that we can revert to previous versions and so that others can reproduce our work and contribute to it. Git is a distributed versional control system that allows us do exactly this. Git runs locally on our computer and it keeps track of our files and their histories. To enable collaboration with others, we can use a remote host (GitHub, GitLab, BitBucket, etc.) to host our files and their histories. We'll use git to push our local changes and pull other's changes to and from the remote host.

Git is traditionally used to store and version small files <100MB (scripts, READMEs, etc.), however, we can still version large artifacts (datasets, model weights, etc.) using text pointers pointing to blob stores. These pointers will contain information such as where the asset is located, it's specific contents/version (ex. via hashing), etc.

Set up

Initialize git

Initialize a local repository (.git directory) to track our files:

git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /Users/goku/Documents/madewithml/MLOps/.git/

We can see what files are untracked or yet to be committed:

git status

On branch main No commits yet Untracked files: (use "git add..." to include in what will be committed) .flake8 .vscode/ Makefile ...

.gitignore

We can see that we have some files that we don't want to push to a remote host, such as our virtual environment, logs, large data files, etc. We can create a .gitignore file to make sure we aren't checking in these files.

touch .gitignore

We'll add the following files to the file:

# Data

logs/

stores/

data/

# Packaging

venv/

*.egg-info/

__pycache__/

# Misc

.DS_Store

For now, we're going to add data to our .gitignore file as well but this means that others will not be able to produce the same data assets when they pull from our remote host. To address this, we'll push pointers to our data files in our versioning lesson so that the data too can be reproduced exactly as we have it locally.

Tip

Check out our project's .gitignore for a more complete example that also includes lots of other system artifacts that we would normally not want to push to a remote repository. Our complete .gitignore file is based on GitHub's Python template and we're using a Mac, so we added the relevant global file names as well.

If we run git status now, we should no longer see the files we've defined in our .gitignore file.

Add to stage

Next, we'll add our work from the working directory to the staging area.

- We can add one file at a time:

git add <filename> - We can add all files at once:

git add .

Now running git status will show us all the staged files:

git status

On branch main No commits yet Changes to be committed: (use "git rm --cached..." to unstage) new file: .flake8 new file: .gitignore new file: Makefile ...

Commit to repo

Now we're ready to commit the files in the staging area to the local repository. The default branch (a version of our project) will be called main.

git commit -m "added project files"

[main (root-commit) 704d99c] added project files 47 files changed, 50651 insertions(+) create mode 100644 .flake8 create mode 100644 .gitignore create mode 100644 Makefile ...

The commit requires a message indicating what changes took place. We can use git commit --amend to edit the commit message if needed. If we do a git status check we'll see that there is nothing else to commit from our staging area.

git status

On branch main nothing to commit, working tree clean

Push to remote

Now we're ready to push the updates from our local repository to a remote repository. Start by creating an account on GitHub (or any other remote repository) and follow the instructions to create a remote repository (it can be private or public). Inside our local repository, we're going to set our username and email credentials so that we can push changes from our local to the remote repository.

# Set credentials via terminal

git config --global user.name <USERNAME>

git config --global user.email <EMAIL>

# Check credentials

git config --global user.name

git config --global user.email

Next, we need to establish the connection between our local and remote repositories:

# Push to remote

git remote add origin https://github.com/<USERNAME>/<REPOSITORY_NAME>.git

git push -u origin main # pushing the contents of our local repo to the remote repo

# origin signifies the remote repository

Developing

Now we're ready to start adding to our project and committing the changes.

Cloning

If we (or someone else) doesn't already have the local repository set up and connected with the remote host, we can use the clone command:

git clone <REMOTE_REPO_URL> <PATH_TO_PROJECT_DIR>

And we can clone a specific branch of a repository as well:

git clone -b <BRANCH> <REMOTE_REPO_URL> <PATH_TO_PROJECT_DIR>

<REMOTE_REPO_URL>is the location of the remote repo (ex. https://github.com/GokuMohandas/Made-With-ML).<PATH_TO_PROJECT_DIR>is the name of the local directory you want to clone the project into.

Create a branch

When we want to add or change something, such as adding a feature, fixing a bug, etc., it's always a best practice to create a separate branch before developing. This is especially crucial when working with a team so we can cleanly merge our work with the main branch after discussions and reviews.

We'll start by creating a new branch:

git checkout -b <NEW_BRANCH_NAME>

We can see all the branches we've created with the following command where the * indicates our current branch:

git branch

* convnet main

We can easily switch between existing branches using:

git checkout <BRANCH_NAME>

Once we're in a branch, we can make changes to our project and commit those changes.

git add .

git commit -m "update model to a convnet"

git push origin convnet

Note that we are pushing this branch to our remote repository, which doesn't yet exist there, so GitHub will create it accordingly.

Pull request (PR)

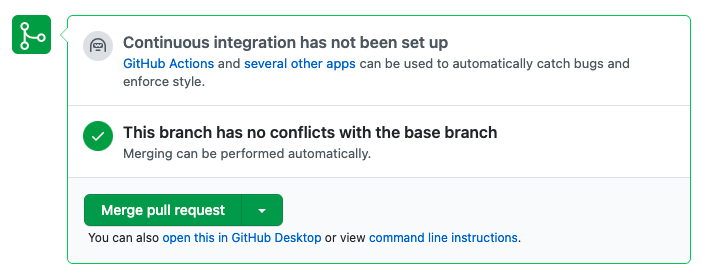

When we push our new branch to the remote repository, we'll need to create a pull request (PR) to merge with another branch (ex. our main branch in this case). When merging our work with another branch (ex. main), it's called a pull request because we're requesting the branch to pull our committed work. We can create the pull request using steps outlined here: Creating a pull request.

Note

We can merge branches and resolve conflicts using git CLI commands but it's preferred to use the online interface because we can easily visualize the changes, have discussion with teammates, etc.

# Merge via CLI

git push origin convnet

git checkout main

git merge convnet

git push origin main

Pull

Once we accepted the pull request, our main branch is now updated with our changes. However, the update only happened on the remote repository so we should pull those changes to our local main branch as well.

git checkout main

git pull origin main

Delete branches

Once we're done working with a branch, we can delete it to prevent our repository from cluttering up. We can easily delete both the local and remote versions of the branch with the following commands:

# Delete branches

git branch -d <BRANCH_NAME> # local

git push origin --delete <BRANCH_NAME> # remote

Collaboration

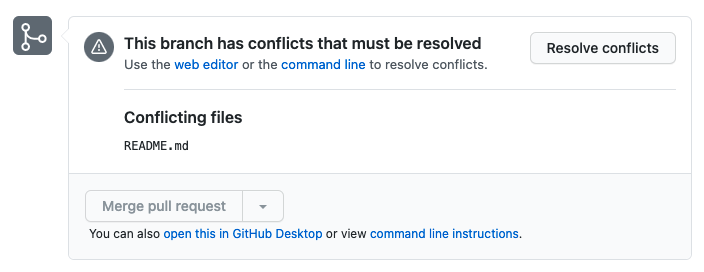

So far, the workflows for integrating our iterative development has been very smooth but in a collaborative setting, we may need to resolve conflicts. Let's say there are two branches (a and b) that were created from the main branch. Here's what we're going to try and simulate:

- Developer A and B fork the

mainbranch to make some changes - Developer A makes a change and submits a PR to the

mainbranch. - Developer B makes a change to the same line as Developer A and submits a PR to

main. - We have a merge conflict now since both developers altered the same line.

- Choose which version of the code to keep and resolve the conflict.

When we try to merge the second PR, we have to resolve the conflicts between this new PR and what already exists in the main branch.

We can resolve the conflict by choosing which content (current main which merged with the a branch or this b branch) to keep and delete the other one. Then we can merge the PR successfully and update our local main branch.

<<<<<< BRANCH_A

<CHANGES FROM BRANCH A>

======

<CHANGES FROM BRANCH B>

>>>>>> BRANCH_B

Once the conflicts have been resolved and we merge the PR, we can update our local repository to reflect the decisions.

git checkout main

git pull origin main

Note

We only have a conflict because both branches were forked from a previous version of the main branch and they both happened to alter the same content. Had we created one branch first and then updated main before creating the second branch, we wouldn't have any conflicts. But in a collaborative setting, different developers may fork off the same version of the branch anytime.

A few more important commands to know include rebase and stash.

Inspection

Git allows us to inspect the current and previous states of our work at many different levels. Let's explore the most commonly used commands.

Status

We've used the status command quite a bit already as it's very useful to quickly see the status of our working tree.

# Status

git status

git status -s # short format

Log

If we want to see the log of all our commits, we can do so using the log command. We can also do the same by inspecting specific branch histories on the Git online interface.

# Log

git log

git log --oneline # short version

704d99c (HEAD -> main) added project files

Commit IDs are 40 characters long but we can represent them with the first few (seven digits is the default for a Git SHA). If there is ambiguity, Git will notify us and we can simply add more of the commit ID.

Diff

If we want to know the difference between two commits, we can use the diff command.

# Diff

git diff # all changes between current working tree and previous commit

git diff <COMMIT_A> <COMMIT_B> # diff b/w two commits

git diff <COMMIT_A>:<PATH_TO_FILE> <COMMIT_B>:<PATH_TO_FILE> # file diff b/w two commits

diff --git a/.gitignore b/.gitignore

index 288973d..028aa13 100644

--- a/.gitignore

+++ b/.gitignore

@@ -1,7 +1,6 @@

# Data

logs/

stores/

-data/

Blame

One of the most useful inspection commands is blame, which allows us to see what commit was responsible for every single line in a file.

# Blame

git blame <PATH_TO_FILE>

git blame -L 1,3 <PATH_TO_FILE> # blame for lines 1 and 3

Time travel

Sometimes we may have done something we wish we could change. It's not always possible to do this in life, but in the world of Git, it is!

Restore

Sometimes we may just want to undo adding or staging a file, which we can easily do with the restore command.

# Restore

git restore -- <PATH_TO_FILE> <PATH_TO_FILE> # will undo any changes

git restore --stage <PATH_TO_FILE> # will remove from stage (won't undo changes)

Reset

Now if we already made the commit but haven't pushed to remote yet, we can reset to the previous commit by moving the branch pointer to that commit. Note that this will undo all changes made since the previous commit.

# Reset

git reset <PREVIOUS_COMMIT_ID> # or HEAD^

HEADis a quick way to refer to the previous commit. BothHEADand any previous commit ID can be accompanied with a^or~symbol which acts as a relative reference.^n refers to the nth parent of the commit while~n refers to the nth grandparent. Of course we can always just explicitly use commit IDs but these short hands can come in handy for quick checks without doinggit logto retrieve commit IDs.

Revert

But instead of moving the branch pointer to a previous commit, we can continue to move forward by adding a new commit to revert certain previous commits.

# Revert

git revert <COMMIT_ID> ... # rollback specific commits

git revert <COMMIT_TO_ROLLBACK_TO>..<COMMIT_TO_ROLLBACK_FROM> # range

Checkout

Sometimes we may want to temporarily switch back to a previous commit just to explore or commit some changes. It's best practice to do this in a separate branch and if we want to save our changes, we need to create a separate PR. Note that if you do checkout a previous commit and submit a PR, you may override the commits in between.

# Checkout

git checkout -b <BRANCH_NAME> <COMMIT_ID>

Best practices

There so many different works to work with git and sometimes it can became quickly unruly when fellow developers follow different practices. Here are a few, widely accepted, best practices when it comes to working with commits and branches.

Commits

- Commit often such that each commit has a clear associated change which you can approve / rollback.

- Try and squash commits if you have multiple before pushing to the remote host.

- Avoid monolithic commits (even if you regularly stash and rebase) because it can cause many components to break and creates a code review nightmare.

- Attach meaningful messages to commits so developers know exactly what the PR entails.

- Use tags to represent meaningful and stable releases of your application.

# Tags git tag -a v0.1 -m "initial release" - Don't delete commit history (reset), instead use revert to rollback and provide reasoning.

Branches

- Create branches when working on a feature, bug, etc. because it makes adding and reverting to the

mainbranch very easy. - Avoid using cryptic branch names.

- Maintain your

mainbranch as the "demo ready" branch that always works. - Protect branches with rules (especially the

mainbranch).

Tags

Leverage git tags to mark significant release commits. We can create tags either through the terminal or the online remote interface and this can be done to previous commits as well (in case we forgot).

# Tags

git tag # view all existing tags

git tag -a <TAG_NAME> -m "SGD" # create a tag

git checkout -b <BRANCH_NAME> <TAG_NAME> # checkout a specific tag

git tag -d <TAG_NAME> # delete local tag

git push origin --delete <TAG_NAME> # delete remote tag

git fetch --all --tags # fetch all tags from remote

Tag names usually adhere to version naming conventions, such as

v1.4.2where the numbers indicate major, minor and bug changes from left to right.

Upcoming live cohorts

Sign up for our upcoming live cohort, where we'll provide live lessons + QA, compute (GPUs) and community to learn everything in one day.

To cite this content, please use:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |